Phileas Fogg, the icy Englishman with a mania for whist and punctuality, was born in 1873, in Jules Verne’s deliciously wry novel “Le Tour du Monde en Quatre-Vingts Jours” (translated that same year into “Around the World in 80 Days”). By 1874, Fogg’s bet-generated circumnavigation of the globe had already found a home on the Paris stage, in a spectacular production that featured a steamship, a live elephant and a locomotive pulling a three-car train.

The “Around the World in 80 Days” that opened last weekend at Penguin Rep gives us all of these people movers and more, but in the modern way: a multitude of characters portrayed by five actors, dozens of conveyances conjured by shifting arrangements of chairs and fabrics, ever-changing scenery communicated by barely any scenery at all. And, somehow, this low-tech approach suffices to evoke Verne’s paean to the technological wonders that had changed his world.

Mark Brown’s clever, lively stage adaptation is faithful to the writer’s voice (at least as it’s come down to us in English) and to the story — even though he makes short shrift of Fogg’s only passion, the bridgelike card game whist, and in the episode Verne bills as “only to be met with on American railroads,” he unaccountably turns Sioux attackers into geographically unlikely Apaches.

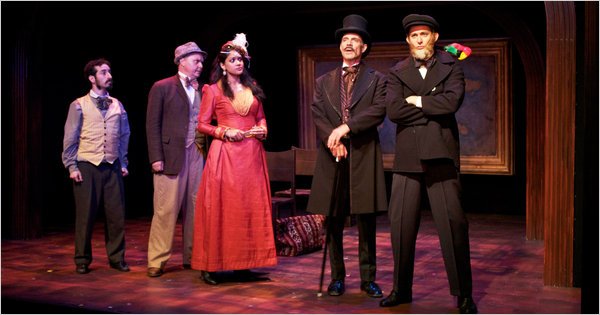

These are minor sins, not to be compared with the impractical, exceedingly un-Fogg-like balloon ride invented for David Niven in the 1956 movie and repeated in both the 1989 miniseries starring Pierce Brosnan and the 2004 remake with Jackie Chan. Happily, Penguin’s Phileas Fogg, Sam Guncler, is impeccably Foggian in his striped vest and precisely tied ascot (Patricia E. Doherty did the fine costumes), and he never boards a vehicle as erratic as a balloon. “The unforeseen does not exist,” he declares curtly, explaining why he is certain that modern transportation would allow him to circle the globe in 80 days.

Of course, his trip consists of almost nothing but the unforeseen, which is what turns it into an adventure rather than an exercise in scheduling. And Penguin’s renovated barn is intimate enough to allow the audience to register Mr. Guncler’s every quiver of surprise, his every raised eyebrow (let it here be noted that Mr. Guncler is ambi-eyebrowed — he can lift the one above his right eye as emphatically as he can the one that frames his left).

Mr. Guncler’s eyebrow gymnastics are matched on a grander scale by the physical exertions of the diminutive Hillel Meltzer as Passepartout, Fogg’s capable French servant. A gifted comedian, Mr. Meltzer deploys an astonishing array of elaborate shrugs, pratfalls and other cartoon contortions, as Passepartout becomes the indispensable facilitator of the show’s comedy as well as of Fogg’s enterprise.

Fogg encounters a variety of functionaries and fellow travelers — all with grotesquely thick accents and distinctive headgear — in the able persons of Andy Prosky and, especially, Michael Keyloun. Mr. Prosky spends most of his time impersonating the crafty and relentless Detective Fix, convinced that Fogg is not an eccentric Englishman on a bet but rather a thief on the run. Mr. Keyloun is particularly memorable as a Monty Python-esque judge and a gun-toting American yahoo with an aversion to foreigners. (I didn’t mind the clownish cowboy or the stereotyped Europeans; I even laughed at the exaggerated French accent that turned “peace pipe” into another, less savory item. But I found myself wincing at some of the jokier Asians and wondering if there wasn’t some way to get laughs without resorting to crude, outdated caricatures.)

Bushra Laskar dons trousers to play a few reporters and such, but her primary role is to enchant Fogg, and us, as Aouda, the beautiful young Indian widow he rescues from her husband’s funeral pyre because it is his duty, and, as it happens, he can spare the time.

The Penguin production, fleetly directed by Thomas Caruso, is performed in front of the large Mercator map and old-fashioned railway clock that dominate Joseph J. Egan’s spare stage set. Zachary Spitzer’s lighting creates 80 days and 80 nights, as well as a typhoon. In 1873, that would have required lots and lots of water. In this day and age, when we can fly around the world in a matter of hours, all it takes is imagination.